Two prevailing themes arise from an analysis of the history of research conducted in the Jornada Basin. These themes are degradation and utilitarian environmentalism. The Jornada (pre 2000) has its roots in the deteriorated range conditions of the region during the later decades of the nineteenth century. Much of its research effort throughout the twentieth century was devoted to developing range-management practices suitable for degraded lands or intensive technologies for their improvement. Even today a central postulate of research is based upon a hypothesis of degradation processes (the Jornada model). Yet, if there is one key deficit to these research accomplishments, it is the failure to identify usable technologies for remediation of degraded conditions.

This failure is probably more a function of the dynamics of our environment, our economy, our attitudes, and our expectations than from an inefficient use of the scientific method. We now believe that remediation has to be accomplished in a more extensive fashion and based on a more complete knowledge of the basic ecological processes that occur in desert rangelands.

Since its establishment, the Jornada's research program has included a significant element devoted to ecological studies. Livestock production and an understanding of the principles for managing the forage on which the range-livestock industry is based was the initial emphasis. However, the emerging principles have an ecological basis. Though an increasing emphasis is now placed on the study of ecological principles, livestock grazing as a viable use and tool for landscape management is still central to the research. This can best be labeled as utilitarian environmentalism, a concern for the long-term capacity to harvest food and fiber from a highly variable (transient) environment. Our terms for this goal, such as "proper use" and "sustainability," have not withstood rigorous examinations. The theme, though, has been and will continue to be how to use this resource based on a thorough understanding of our surroundings and our interactions with those surroundings.

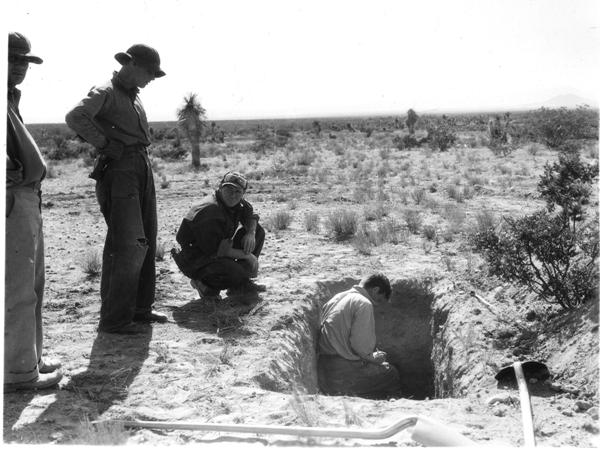

Half a mile north of PSCS number 8 old alluvial fan. Men digging hole. General aspect of Yucca elata island surrounded by Covillea type, half mile north of plant soil study number 8. An old alluvial fan of coarser-more porous material which is high in lime content but only very loosely cemented in contrast to the Covillea area that is underlain by hard caliche. April 28, 1936. (More historic photographs can be seen at https://jornada.nmsu.edu/jornada/photo-gallery.)

HISTORY AS ANALOG - The history of research results from the Jornada supports three emerging postulates from the broader body of rangeland science in recent years. These postulates are (1) many ecological processes have thresholds below and above which they become discontinuous, chaotic, or suspended; (2) ecological character is reflected by dominant species; and (3) species are interdependent and many of these interdependencies form highly specialized interactions.

Many of the observations in the Jornada Basin during this century have documented surprisingly rapid changes across the landscape. Yet, our frustrations in effecting change, even with intense inputs, supports the second postulate. Remediation within this ecosystem will require specific knowledge of species interactions, which may have to be regenerated before corrective management actions will be effective. Needless to say, we can predict from our observations that simply abandoning the landscape will not promote recovery or prevent further deterioration.

Within this context, livestock grazing must be managed so as to neither disrupt species interactions or drive impacted processes beyond the thresholds. The average annual carrying capacity for this hot desert is 9.5 animal units/section. This would require the annual harvest of approximately 10-20 g of forage per m2 with even distribution of grazing use. We have the basic management techniques for controlling grazing for this level of defoliation. However, we still need the ability to effectively monitor that use over large areas, detect impacts of use on key processes, more rapidly recognize seasonal forage dynamics, and develop methodologies for using the animal to effect desired changes.

CONCLUSIONS - Much of the research conducted during the early twentieth century is still applicable to today's management issues. Though the experimental designs employed in the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s might not entail the sophistication serviceable by current statistical analyses, the thoroughness and detail of the early field research more than compensate. In addition, the length of the research record itself becomes a powerful tool for insight and scientific speculation.

One perception that surfaces from a review of the research record of the Jornada Basin is the complexity of this arid ecosystem. This complexity cannot be easily communicated. Yet, these desert rangelands will continue to provide critical resources to a significant portion of the human population. It is important that we not oversimplify our understanding of this system in our attempts to communicate our knowledge to interested segments of our society. Solutions to today's management problems are generally not simple, and we should not create false expectations. We need to use the full scientific history of experimental stations like the Jornada to create more complete understanding. This should be a prominent objective within our research programs. In fact, using the Jornada Experimental Range as a demonstration for our knowledge of desert rangelands was an original objective of C. T. Turney and E. O. Wooton, and it is still valid today.

In 2006 a synthesis book (Havstad et al. 2006) was published that summarized nearly a century of research at this location. The following sections of "Our History" provide a description of this scientific program at the end of the first decade of the 21st century.